|

|

In Search of Ancient Seafarers

A Marine Archaeological Reconnaissance in

the United Arab Emirates

By Chris Kostman, M.A.

Originally published in IANTD Journal, International Association of Nitrox and Technical Divers, Vol. 95-3; Berkeley Archaeology, Vol. 2, No.2, April 1995; Immersed, Fall 1996.

Want to write or rewrite history? Find a shipwreck. The underwater world has proven to be a treasure trove of archaeological and historical riches for many centuries. Essentially every man-made product has at one time or another been borne across the waters in the fragile trade of seafaring, thus providing time capsules for those intrepid explorers who have combed the seafloor in search of the remains of some ocean voyage gone astray.

The two most productive world regions in the endeavour of marine archaeology are the Mediterranean and the Caribbean seas, their seafloors consistently giving up items and information that have allowed the writing and rewriting of many a history book, and the filling to overflowing of many a museum. So prevalent are wrecks in those areas, and the explorers so equally prevalent, that efforts are often made to search for a specific shipwreck, or a wreck of just a specific century. The two most productive world regions in the endeavour of marine archaeology are the Mediterranean and the Caribbean seas, their seafloors consistently giving up items and information that have allowed the writing and rewriting of many a history book, and the filling to overflowing of many a museum. So prevalent are wrecks in those areas, and the explorers so equally prevalent, that efforts are often made to search for a specific shipwreck, or a wreck of just a specific century.

Not so in the Arabian Gulf and the adjacent regions of the Indian Ocean, an area of the world with a seafaring tradition of over 5,000 years, yet which has gone essentially unexplored beneath the waves. In fact, the South and Southwest Asian regions, and the Gulf area in particular, have perhaps the richest and longest running seafaring tradition of any world region. From before and through the Bronze Age, Iron Age, rise of Islam, medieval period, on down into the 20th century, ships in this region have played a vital and pivotal role in commerce, communication, and exploration.

My career goal is the discovery, excavation, and documentation of a Bronze Age (c.5,000 - 3,500 years ago) ship involved in the elaborate trading activity between Sumer (Iraq), Magan (southeastern Arabia), Meluhha (Pakistan), Dilmun (Bahrain and northeastern Arabia), and the regions between and beyond. My search zone for this shipwreck: the Arabian Gulf, a body of water no deeper than 300 feet and encompassing a mere 90,000 square miles. With these relatively shallow depths, coupled with the great strides made in technical diving in recent years, no area of the Gulf is beyond the reach of surface diving. This could be a bounce dive to take a quick look at something unusual detected by sonar or ROV (remotely operated vehicle) or the actual excavation of a wreck.

This career goal of mine was fashioned over the last eleven years of studies in the field and at the University of California at Berkeley. There I had the good fortune to study for five years under the late George Dales, a real life Indiana Jones. I completed both B.A. and M.A. degrees in South Asian Civilization with Dr. Dales' mentorship between 1985 and 1992, including a four month field season excavating at Harappa, Pakistan. This site is one of the twin capital cities of the Indus Valley Civilization, which flourished in the Bronze Age (app. 3,000 to 1,5000 B.C.) in what we now call Pakistan and northern India.

Dr. Dales, who passed away just one month before I received my M.A, degree, was a leading scholar of the fascinating and enigmatic Harappan or Indus Valley Civilization. This utopian and literate society, contemporary to Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, built great cities and public works, but was seemingly free of warfare, social stratification, and, possibly, religion. Dr. Dales' original studies in the 1950's and 1960's focused on the ancient Near East, Mesopotamia and its environs, but his graduate advisor, Samuel Noah Kramer, advised Dr. Dales to "go east, young man" to focus his career on the little known Indus Valley.

Some thirty years later, as Dr. Dales' final student and apprentice, I became increasingly interested in the trade, exchange, and contact between the Indus Valley and the ancient Near East. With my firm background in both regions, my training as a scientific diver, and a sincere interest in doing original work in the study of the maritime contact between the two regions, Dr. Dales' final words to me were to "go west, young man." Some thirty years later, as Dr. Dales' final student and apprentice, I became increasingly interested in the trade, exchange, and contact between the Indus Valley and the ancient Near East. With my firm background in both regions, my training as a scientific diver, and a sincere interest in doing original work in the study of the maritime contact between the two regions, Dr. Dales' final words to me were to "go west, young man."

And it so it was that my current advisor, David Stronach, another real life Indiana Jones and a specialist in ancient Iran and Iraq with whom I have been studying for five years, helped me to join a research project in the United Arab Emirates in 1993/1994. This project, a joint expedition between the University of Sydney, Australia and Hampshire College in Amherst, MA was led jointly by Dr. Dan Potts of Sydney and Dr. Debra Martin of Hampshire. This expedition's goal was to excavate four tombs of approximately 5,000 years in age with the intention of recovering human skeletal remains and associated artefacts in the hopes of furthering our understanding of this recently "discovered" part of the world. Potts and Martin's other UAE projects had unearthed artefacts from the Indus Valley and other distant points, proving the UAE sites' role in long distance trade. My specific role on the project would be to help identify objects from the Indus Valley, as well as utilize my Urdu language skills in communicating with the Pakistani excavators with whom we'd be working.

Besides contributing to this project directly, my not hidden ulterior motive in joining the team was to use the opportunity to network with the local archaeological authorities in the hopes of beginning a search for ancient shipwrecks in the UAE's territorial waters. So, as I packed for three months of excavating in the Arabian Desert, I also took along my diving gear and basic marine archaeological reference materials written by George Bass and Willard Bascom.

It worked. After my three months with the Sydney/Hampshire team were completed, I had the good fortune to initiate a search for submerged shipwrecks of any period in the coastal and territorial waters of the United Arab Emirates. The UAE's strategic location on the Arabian peninsula, adjacent to the Straits of Hormuz, is at the confluence of trading routes extending from China, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and India in the east, to Ethiopia, Egypt, and Europe in the west. This location, as well as the country's own rich cultural heritage, make this an ideal region in which to search for ancient seafarers. Furthermore, a shipwreck has much more to offer than a tomb in archaeological value: while tombs contain only those objects intended to be left behind, shipwrecks can contain anything and everything. In effect, wrecks leave behind snapshots of reality, while funerary artefacts provide just idealized postcards.

My multidisciplinary team of Berkeley scientific divers included marine biologist Kyler Abernathy, historian Sean Hathaway Kelly, and myself. Our project is supported by the University of California at Berkeley, Archaeoscience International, and the ruling Shaikhs of the Emirates of Fujairah and Sharjah, who have a sincere interest in understanding more about their country's cultural heritage.

Our research and search methods involved all of the basic nuts and bolts of searching for shipwrecks from a time and place with little or no historical records to steer the searchers:

- Studying the historical and popular records of shipping lanes, ports, and commercial areas.

- Collecting maps and charts of the coastal regions and adjacent sealanes, as well as U.S. Navy seafloor soundings.

- Surveying the coastlines by Land Cruiser and foot to catalogue likely ports of call and dangerous coastlines.

- Surveying the coastlines by boat and scuba diving to establish a knowledge base of water conditions, tidal patterns, seafloor depths and geological makeup.

- Surveying the coastlines by helicopter to visually search for wrecks or likely wreck-producing areas.

Our initial season in the UAE allowed preliminary searches of the UAE's east coast along the Indian Ocean in the Emirate of Fujairah, and selected west coast sites and islands of the Arabian Gulf in the Emirate of Sharjah. In both regions we catalogued coastal sites once (and often still) a part of the maritime trading routes.

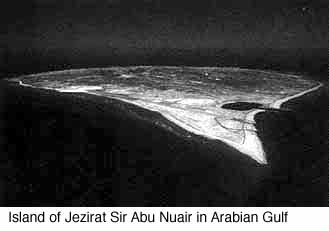

We also flew out to Jezirat Sir Abu Nuair, a Sharjah-owned island in the Arabian Gulf, where a construction company digging out a small fishing harbor on the island had unearthed an Iron Age (app. 1,500 B.C.) ceramic vessel of Iranian origin. This was our clue that perhaps more could be found and learned on the island. Here our carefully planned foot survey of a coastal area led us to the discovery of a number of pottery fragments ranging in date from 100 to 1500 years ago. We also identified an Islamic Period cemetery previously unknown to the Sharjah Department of Antiquities. These finds, along with the Iron Age ceramic vessel, are proof positive of continual maritime activity for thirty centuries on just one small island.

We will continue our efforts in 1996 and beyond, with the aim of pinpointing very specific target areas in which to search for shipwrecks in a more detailed manner with the use of side-scanning sonar and ROV. Furthermore, we will return to Jezirat Sir Abu Nuair, studying it further both on- and off-shore. We will also search areas of the UAE's Sharjah coastline rumored to conceal sunken villages. Additionally, we will continue to catalogue, study, and possibly excavate on-land, coastal archaeological sites to help further elucidate the patterns of maritime activity in antiquity.

This archaeologically-focused survey is taking place within a multidisciplinary context, so we are also studying anything that strikes us as interesting in terms of the entire marine and coastal setting. This includes abandoned fishing villages, ship and harbor design, and coastal irrigation and drainage systems. Taking this multidisciplinary approach a step further, we are also considering the coastal and marine geology, geomorphology, marine biology, and environmental setting. For example, rates of sedimentation, tectonic movement, and the like are critical to our understanding of potential marine archaeological discoveries, as well as useful and important considerations in and of themselves.

Though our first efforts in the UAE have been timid and of a broad stroke, we are laying the scientific and archaeological groundwork for greater discoveries to come in future seasons. There are, quite assuredly, ancient ships, artefacts, and possibly even sunken villages to be found in those waters, and we intend to find them. Furthermore, the United Arab Emirates is a wonderful and fascinating country and it is my plan to contribute significantly to the local and worldwide understanding of the UAE's rich cultural and environmental heritage.

Note: This research project owes an immense gratitude to the generous support of H.H. Dr. Shaikh Sultan Muhammad Al-Qasimi, H.H. Shaikh Hamad Bin Mohammed Al Sharqi and H.H. Shaikh Salah Bin Mohammed Al Sharqi; the Departments of Cultural and Archaeological Affairs of the Emirates of Sharjah and Fujairah, UAE; the Stahl Travel Fund, Department of Near Eastern Studies, and Office of Scientific Diving at the University of California at Berkeley; and the Dr. Karl Koenig Foundation.

More Archaeology Articles by Chris Kostman.

|